I’ve worked with Databricks for more than a decade now, and it amazes me how it evolved exponentially from a simple Spark workspace into a full platform for data engineering, ML, analytics, and now AI. With features like Genie, Databricks Assistant, code-generation tools, and Lakehouse AI, it’s become the place where I do almost everything—from pipelines to experiments—without ever feeling like I’m switching contexts.

1. Understanding Delta Live Tables (DLT)

Delta Live Tables (DLT) is Databricks’ declarative framework for building reliable, incremental pipelines. Instead of wiring jobs together manually, DLT takes care of dependency ordering, checkpoints, schema handling, and data quality rules. It focuses on correctness and consistency, and because it sits on top of Spark, it still follows Spark’s execution and resource model.

As a data engineer, I lean on DLT constantly to bring event streams into the Lakehouse, clean and transform them, and turn them into dashboards and insights that different teams depend on. It’s my go-to way of making raw events useful.

But there’s one place where I found the behavior gets interesting—and sometimes surprising: when multiple downstream branches in a pipeline kick off at the same time.

2. My Scenario: Two Branches from One Streaming Table

I had a single streaming table containing real-time “transaction events”—each event representing a user requesting something that is provided by one of our vendors. From this one stream, I needed two completely different analytic outputs:

(1) User Statistics

- unlock counts per user

- success/failure ratios

- daily/weekly engagement

- user-level activity scoring

(2) Vendor Statistics

- volume per vendor

- vendor-level success rates

- operational KPIs

- anomaly patterns for vendor outages

Almost all the cleaning, enrichment, and transformations happened on this main event stream, so it made sense to keep everything inside a single DLT pipeline. The logic was shared up to a certain point, and later the stream needed to split into two: one branch focused on user-level metrics, and the other on vendor-level metrics. The transformation logic, keys, and aggregations were entirely different between them.

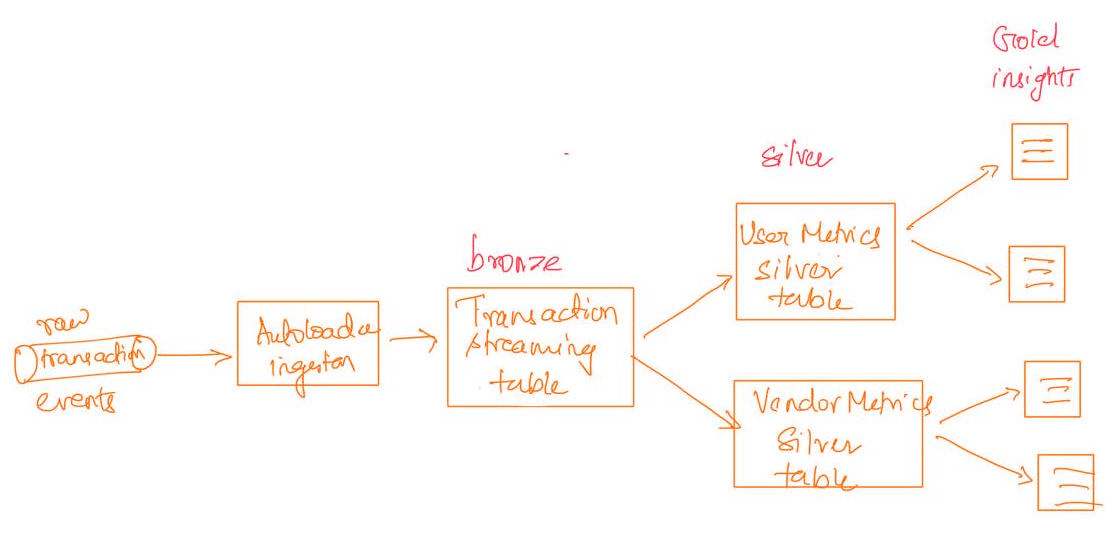

The DAG looked like:

Figure 1: Two branches reading from a single streaming table

It was clean, modular, and functionally correct.

But the pipeline ran much slower than expected.

3. Branching Was Super Slow during initial snapshot

When both branches ran at the same time during the initial snapshot, the pipeline made almost no progress — it ran for over 27 hours, consumed a lot of cluster resources, and still had barely advanced.

What was interesting was that:

- This extreme slowness only occurred during the initial snapshot or full-refresh, where the entire dataset needed to be computed.

- Once the pipeline moved to incremental processing, both branches ran efficiently and without issues.

- The parallel execution during the initial snapshot was actually slower than running the same two branches sequentially, even though sequential execution logically does more total work.

In short, parallelism hurt the initial load instead of helping it.

4. What caused the pipeline to stall

DLT schedules both downstream transformations as separate Spark jobs that run at the same time.

This created:

- excessive garbage collection (GC)

- memory pressure

- spills to disk

- shuffle congestion

- competition for CPU, memory, and I/O

In other words, the cluster was overloaded by two large jobs running at once.

Running them in parallel caused both to slow down dramatically.

5. The Fix

For the initial snapshot or any large backfill, the simplest solution is:

Option 1 — Increase cluster resources

Give both branches enough memory, CPU, and shuffle capacity to run together. Scale back down for successive incremental runs.

Option 2 — Run the branches sequentially

Let one branch finish completely before running the next.

This avoids resource contention and makes the initial load predictable and efficient.

6. Conclusion

Once the snapshot is complete and the data becomes incremental, running both branches in parallel works fine. Incremental batches are small, each update touches only the newly arrived data, and the resource load is minimal. At that point, the workload no longer competes heavily for memory or shuffle, and parallel execution behaves exactly as expected.

With the initial load handled carefully (either by scaling up or running sequentially), the pipeline becomes stable, predictable, and simple to maintain. Parallel branches are perfectly fine for day-to-day incremental processing; it’s only the very first large computation that requires a bit of extra attention.